Youth Ambassador Isobel Archer completes her four-part blog series by looking at why modern slavery persists.

- 45.8m people

- Second-largest criminal industry

- Fastest-growing industry

- Profits of $150bn

I started this blog series reciting these statistics. Modern slavery is a huge industry that affects a large amount of people. Why is it then, that repeated efforts to engage and inform civil society about modern slavery have faced such difficulty? Why do the numbers remain so high?

In 2013 Police Scotland launched their information leaflet “Human Trafficking – Reading the Signs”; in the same year the Northern Ireland Organised Crime Task Force published their “Human Trafficking: Know Your Rights” leaflet; in 2014 the Home Office launched their “Slavery is Closer Than You Think” campaign. Yet despite these awareness-raising initiatives and attempts to push human trafficking into the limelight, public perception remains almost unaffected. For example, “Reading the Signs” is estimated to have reached 93% of the population, yet the proportion of people acknowledging the existence of modern slavery only increased by 11% to 63% of the population.

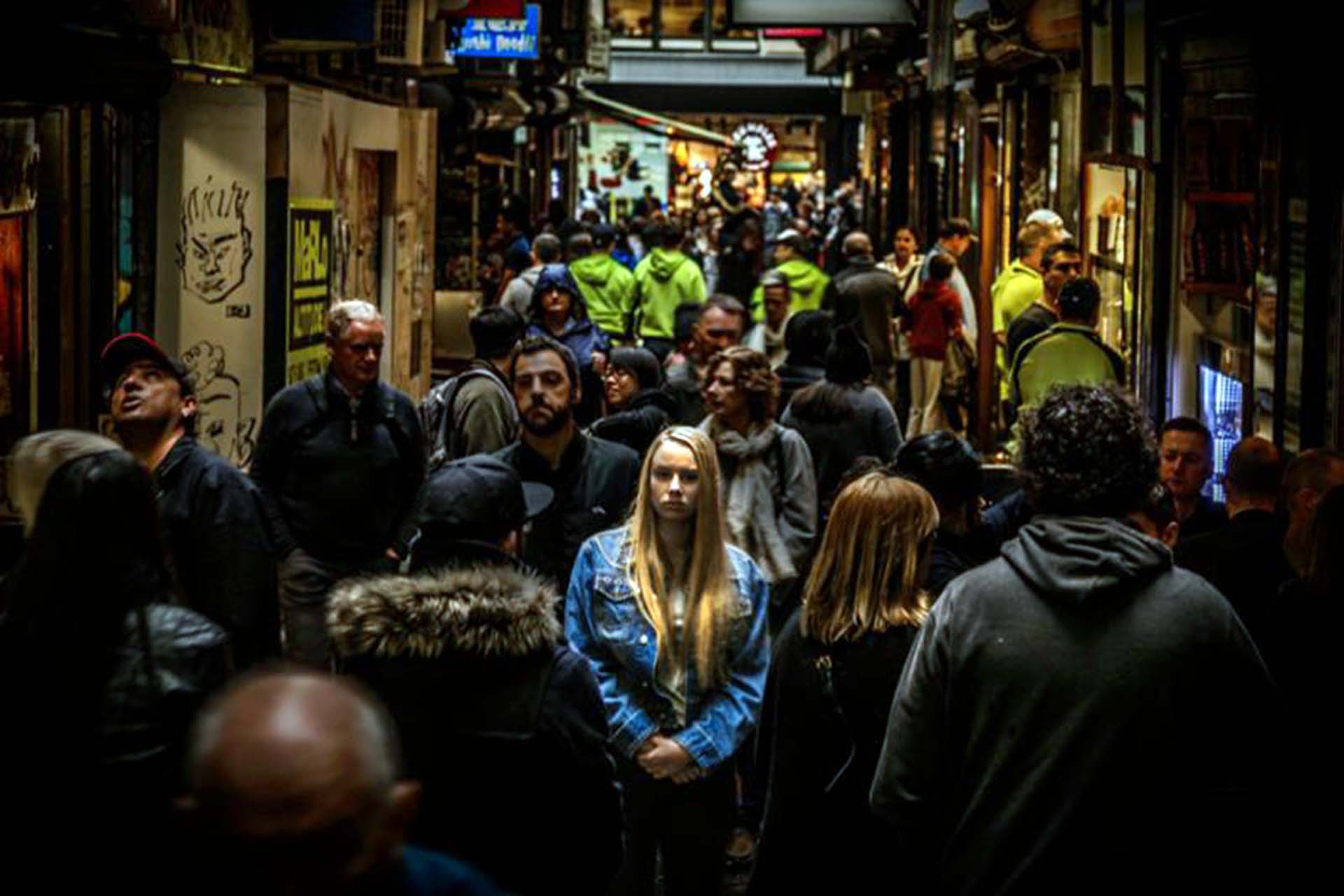

Possibly the most obvious and understandable reason for such a low response from civil society stems from modern slavery’s invisibility. Previously, I discussed the problem of convincing the public of modern slavery’s invisible chains – we don’t need physical restraints to trap, control and manipulate a person. The result is a recurring mismatch between understandings of emotional and psychological abuse and public misperceptions. The result of general misunderstanding of signs and symptoms is a failure to correctly spot, recognise and report the signs of trafficking. The actual numbers of people trafficked are consequently hard to obtain and we rely mostly on varying statistics. With a lack of hard evidence to present to the public, people are unaware of the prevalence of slavery today; whilst most people remain oblivious, reporting is kept low. Without evidence, people are less likely to understand or believe it happens. The cycle is difficult to break.

Further, the conflation of human trafficking with other crimes mean that law enforcement and civil society are less inclined to treat modern slavery as a distinct offence in itself. At the Trust Women Conference last week, Anti-Slavery Commissioner Kevin Hyland once again called for the end to the merger of modern slavery and illegal immigration. However, time and time again, it is all too frequently confused with organised crime categories like people smuggling. Unsurprisingly, as a result of the ongoing migrant crisis in Europe, there is an increased focus on migration more generally, but both political and public focus is primarily on illegal immigration. Any form of cross-border movement by people without authority or documentation is perceived, both politically and publicly, as illegal immigration. Human trafficking is pushed into the shadows and engulfed by the hysteria surrounding migration

With the implementation of the Immigration Act 2016, a focus on labour exploitation has been overshadowed by a focus on illegal labour. The Act makes any form of illegal labour first and foremost a criminal offence, regardless of whether the worker is a being held as a slave. Far from regarding trafficked people as passive victims, the Act turns slaves into active participants in illegal labour, criminalising them and disregarding their human right to be free from slavery. Consequently, victims are dissuaded from speaking out, and traffickers are incited to continue exploiting people as slaves.

Finally, there is a misconception that slavery is something that exists elsewhere and not in the UK. Additionally, there is a reluctance to interfere when a situation involves someone from another culture, religion or ethnicity – abuse has been written off in certain cases with the excuse that the behaviour must be part of “normal” cultural practice. Victoria Climbie’s murder in 2000 shed light on the hesitancy of social services when political correctness took precedence over the protection of victims. This infamous case became well known for its importance in establishing safeguarding networks across social services, law enforcement and schools. Less known is that the case was actually an instance of human trafficking by way of private fostering. Hiding inaction behind a veil of cultural relativism is never tolerable, and until we encourage people to accept that slavery is cross-culturally unacceptable, political correctness and anxiety around being called racist or intolerant is arguably one of the biggest silencers of those who unwittingly witness human trafficking in the UK.

Essentially, what these problems of the misconceptions surrounding modern slavery highlight is a lack of general awareness. Even when numerous sources of information are publicly available, the crux of the problem seems to be the equation of “illegal immigration” or cultural “difference” with the reality of human trafficking. And that’s on the rare occasions slavery is visible and recognised.

How then do we combat this? Lack of knowledge can only be countered by continued education and open dialogue on the subject. By exposing the means by which modern slavery occurs and engaging with the reality of the crime in a meaningful way, ending modern slavery can become a defining feature of our age.